摘要:在本论文中,笔者将探讨对“世界城市”的研究如何有助于将城市研究扎根于全球化的辩论之中。关于世界城市的文献广泛讨论一系列问题,采用了不同的本体论、认识论和方法论。这些文献共同加深和扩展了我们对以下问题的理解:第一,某些特别的城市如何在全球化经济/社会组织中作为一个关键平台。第二,这如何影响这些城市内部的社会空间变化。然而,由于这些文件缺乏一个中心范式,即便是被广泛引用的文献也被认为是日益多样化的研究全球城市文献中的具体部分。本文回顾了世界城市的核心概念以及这些概念如何变得越来越广泛和富有争议;世界城市形成的时空和组织维度;讨论了基于生产者服务公司办公网络地理的世界城市图谱;并描绘了未来的主要研究议程。

关键词:全球化、全球城市、网络

作者简介:Ben Derudder, Professor of Human Geography in the Department of Geography at Ghent University.

·Conceptualisation

The idea of a global economy articulated through cities is longstanding, but the specific suggestion of a set of “world cities” having a strategic role in the coordination and control of the global economy is relatively new. In spite of some earlier contributions and a variegated genesis of the concept, contemporary research on world cities is most commonly traced back to a handful of writings in the 1980s. The theoretical raw materials of this then-emerging literature are most clearly articulated in John Friedmann’s “World-city Hypothesis,” in which he identifies world cities as those centres from which the “new international division of labour” created by multinational enterprises was being organised and controlled. In the 1990s, a more encompassing language of “globalization” emerged as the conceptual backdrop for many research of the fields of social science, and the world cities research agenda blossomed as one of the possible takes on how globalization and cities intersected. This resulted in a more varied conceptual and empirical literature (alongside a more complex terminological toolkit), in which—alongside Friedmann’s seminal paper—Saskia Sassen’s “The Global City” arguably came to serve as a key reference point for the literature at large.

The unambiguous connection between writings on “world cities” and on “globalization” implies that the former literature has been a major laboratory for contemporary theories, methodologies, and intellectual frameworks developed in the latter literature. Major examples include vigorous and wide-ranging debates on the potential of post-structuralist thinking on, and post-colonial readings of globalization, as well as on the modified role and relevance of national states under conditions of contemporary globalization. Importantly, debates on the cities/globalization-nexus have moved well beyond the “world-city” terminology, with new frameworks such as “planetary urbanization” and a more encompassing language of “globalizing cities” being developed. Nevertheless, in spite of the term “world cities” (and what it conceptually engenders) frequently being contested and purposely bypassed, it has clearly become a major rallying point in social science research on globalization in general and its urban studies dimensions in particular. The purpose of this paper is to review the most germane elements of this literature.

Drawing out the fundamental elements of the world-city literature is not an easy task. This is because casual references to a “world-city and especially “world-city theory” tend to overstate the coherence of the scientific literature invoking that term. Instead, following Saey’s assessment of the disparate roots of world cities research, it seems more apt to think of different perspectives unevenly coming together in this literature, and thus most certainly do not add up to a paradigm in a Kuhnian sense. Nonetheless, it seems fair to state that the most important(in terms of output) of the different threads running through the world-city literature is a political-economic approach that aims to (1) understand urban nature of the (production of capabilities for) economic, political, cultural and societal control at the global scale, after which (2) attention is paid to what this entails for the urban fabric of cities that are central in this regard. Sassen’s “The Global City” is a case in point, as the book fundamentally deals with (1) how the rise of producer services economies catering to a global economy in a de facto limited number of cities is related to global power structures, after which (2) this is related to the changing nature of inequality in these cities. Many other examples dealing with very diverse elements at the nexus of global control/urban change could be listed, but for the sake of this paper the key point is that is the major focus of this literature. Given this, in the remainder of this paper I largely restrict myself to this unique take on “world cities”.

Nonetheless, it is important to note from the outset that even within this take on “world cities” diversity reigns. Indeed, neither Sassen’s book nor its subsequent use as input to other research can be taken to be a wholesale depiction of the world-city literature, which is characterized by a pronounced pluralism. This is clear from the wide variety of research topics, epistemologies, and methodologies marshalled in the literature. As van Meeteren et al. highlight, world-city research encompasses both model-based approaches and qualitative research methods for understanding cities within contemporary globalization. Some conduct detailed empirical studies on specific (sets of) cities, while others advance a more theoretical approach. Furthermore, some authors emphasize structure, while others underscore agency, Some focus on issues of global capitalist expansion, while others have a strong interest in methods for analysis and visualization.

Additionally, in line with the two tiers of attention in Sassen’s book, certain scholars primarily try to understand the remit of the notion of (capabilities for) global command and control, while others mainly deal with socio-spatial changes within cities and/or the politics of world-city formation “on the ground”. Importantly, within this diversity there are also plenty of authors who critically examine the applicability of world-city frameworks to less-obvious cases. And finally, world-city research is still a fast-developing field of literature. For example, the second edition of “World-city Network” is not simply an update of a variety of empirical patterns in the analysis of the global connectivity of world cities, but represents a comprehensive revision that involves engaging with new developments, critiques, refined and improved methods, as well as a broader appreciation of how the research relates to other urban and globalization studies. In light of this diversity and continuing developments, Acuto and van Meeteren et al. propose to think of the world-city research agenda as being produced by an “invisible college”. An invisible college refers to the sociological formation of a group of authors in a particular research field who constitute a social circle, but have varying degrees of involvement on the basis of diverging research interests. This circle has an informal stratification, and is characterized by internal disagreements, debate, and openness to internal mavericks and criticism. As such, a journal such as xx and an institution such as xx can play an instrumental role in nurturing and further developing this diversity. In the remainder of this paper I review the main dimensions of this literature by subsequently discussing spatiotemporal and organizational of world-city-formation; presenting a straightforward case study of how world cities can be mapped; and the future of this research domain.

·Spatiotemporal dimensions

In spite of the marked diversity in the literature, research on world cities seems premised on two key observations. First, the increasingly worldwide redistribution of economic, political, cultural, and societal activities necessitates strategic control functions that are found in a limited number of locations: globalization in its various guises has led to increased levels of geographical complexity, and this calls for control points to ensure the smooth functioning of the global system. In other words: world cities contain a disproportionate number of strategic agents in the global system (e.g. headquarters of multinational corporations and international institutions, specialized and internationalized business firms, cultural industries, non-governmental organizations). Second, this practice of strategic control is accomplished through the capacity of these world-city-agents to network across space. In addition to developments in logistics and airline connectivity facilitating the flows of goods and people, from the 1970s onwards advances in two distinct technologies—computers and communications—combined to create a new enabling infrastructure for global organization that has been instrumental for world-city-formation. As infrastructures and technologies became more pervasive and sophisticated, this global infrastructure implied that spatial organization became increasingly conceptualized through networks (in which interaction is defined by quasi-simultaneity) to the detriment of territoriality (in which interaction is defined by proximity). Envisaging world cities in the context of a “network society” particularly gained momentum in the 1990s, when influential authors such Manuel Castells claimed that globalization processes are basically all about transnational processes operating through numerous networks, with networks between world cities as a prime example of this logic.

In any case, fundamental contributions to the world cities literature are loosely united in their observation that cities such as New York and London derive their importance from a privileged position in networks of capital, knowledge, ideas, and people. Furthermore and as already suggested, they commonly refer to the effects of the increasing internationalization of trade and production, give some weight to the increased service intensity in all sectors of economic, cultural, social, and political life, and identify the relevance of recent evolutions in transport and technology. However, at the same time, it is quite clear that such a sweeping approach rings rather hollow. Teasing out the spatiotemporal dimensions of world cities is thus best achieved by more concretely exploring how key contributors position themselves with respect to (1) the main function of cities; (2) the key agents in the formation of world cities; (3) the global structure that thus emerges; and (4) the impacts on the ground. In the remainder of this section, I will focus on the first two points; the latter two will be dealt with in the subsequent sections. That is, here I will briefly single out the spatiotemporal dimensions of world-city-formation by exploring the major vantage points of what are arguably the two most formative contributions in this literature, i.e. those by Friedmann and Sassen. Friedmann frames the emergence of world cities in the context of a major geographical transformation of global production and the ensuing complexity in the organizational structure of multinational enterprises. The increased economic-geographical complexity associated with contemporary globalization, which he argues, requires a limited number of control points, and world cities are considered to be such points. A world-city is a spatially integrated economic and social system at a given location or metropolitan region and can therefore even refer to polycentric urban regions rather such as the Kansai Region or Randstad Holland. Friedmann gives theoretical body to his “framework for research” by (implicitly) subsuming it under Wallerstein’s world-systems analysis, hence the title of Knox and Taylor’s “World Cities in a World-System”. This implies a vision of globalization that emphasizes the presence of a worldwide system where economic development involves hierarchical and spatial inequalities based on the concentration of relatively monopolized and therefore high-profit production of a limited number of “core” zones. World cities are deemed to be the key organizational nodes in the networks of power and dominance that (re)produce global inequality. Although no systematic analysis of the global geography of world cities was attempted, Friedmann provided a schematic (and now almost iconic) outline of how this geography looked like, differentiating between primary and secondary cities in core and semi-peripheral countries (e.g. New York City primary/core; Sydney secondary/core; Sao Paulo primary/semi-periphery; Bangkok secondary/semi-periphery). Although Friedmann points out that the economic variable of command-and-control is likely to be the decisive, world cities can show up as be seen as the locales from which other forms of global power are projected, e.g. geopolitical and/or ideological-symbolical control. Miami-s control position over Central America is a case in point, as is the position of Los Angeles in the production of global consumer identities or Berlin in defining “global culture”. Recently, Shanghai’s explicit global positioning by teaming up with UN Habitat to create a “World Cities Day” where attention is paid to both sustainability and culture can be interpreted along similar lines projecting a specific notion of power into the world.

In“The Global City”, Saskia SassenS. Sassen, The Global City. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991. presents an alternate take on the role of world cities in the global economy, and does so by focusing upon the attraction of producer service firms to major cities that offer knowledge-rich and technology-enabled environments. In the 1980s and 1990s, many such service firms followed their global clients to become important multinational enterprises in their own right, albeit that service firms tend to be more susceptible to the agglomeration economies offered by major city locations. Sassen thus advocates a shift of attention to the advanced servicing of worldwide production, which implies a shift in focus from formal command power in the global economy to “the practice of global control: the work of producing and reproducing the organization and management of a global production system and a global market-place for finance”. Through their transnational, city-centred spatial strategies, producer service firms have created worldwide office networks covering major cities in most or all world regions, and it is exactly the myriad of connections between these services complexes that gives way to a global urban system centred on world cities. Although, not unlike Friedmann, Sassen herself has not attempted a systematic mapping of the global geography world cities, and she suggests a break away from rigid core/periphery thinking by stating that the geography of world cities will likely cut across established North/South divides. Not unlike Friedmann, this is an approach that has a strong economic bent, but here too similar arguments have been made regarding different types of agents that follow a similar logic, including sports federations, non-governmental organizations, maritime and logistics firms, real estate firms, architects, etc.

Some critics have questioned the Friedmann/Sassen and their followers take on world cities. They argue that it is both naive and problematic to even if implicitly trace the causal dynamics of world-city-formation back to a combination of globalization and changes in transportation and communication technologies. Massey emphasizes that the primary task of global/urban researchers should be to focus on the politics of the how and why of, say, the emergence of the New York-London axis as the organizational backbone of the global economy. To frame this critique, it is useful to think of research on world cities as part of broader social-scientific narratives on the resurgence of cities as key territorial units within contemporary globalization. Key examples of such city-centred narratives of an increasingly globalized economy and society are Edward Glaeser’s “If Mayors ruled the World,” in which straightforward and normative arguments are presented for an unavoidable and imminent urban future. In spite of their disparate roots and despite covering very different topics, such books tend to share an undercurrent of the “objective need” for a new strategic economic and political role for cities against a backdrop of economic deregulation, liberalisation, and privatisation, thus de facto considering this neoliberal backdrop as an undisputable given.

From this vantage point, world-city research in its most uncritical form, with its focus on recounting the global centrality of cities, can also be cast as naively describing, and therefore subscribing to, neoliberal globalization. It is therefore no surprise that critics such as Michael Peter Smith primarily and dismissively label world cities alongside globalization as a social construct, arguing that research should focus on critically dissecting the genesis and the adoption of the concept more than anything else. The uneven and partial adoption of “world-city research” in urban policy frameworks would point to the relevance of such a critical perspective. For example, “world-city league tables” have become popular amongst policy-makers and global firms alike, with the image being ‘consumed’ and ‘internalized’ largely stripped of its critical antecedents. Being aware of the potential performativity of knowledge has certainly become a major point of attention for world-city researchers. However, in tune with Van Meeteren et al., I believe it is useful to not be too much stifled by this: neoliberal urban development in general and processes analysed under the “world cities” rubric in particular would very likely have occurred anyway, and stopping researching it may simply mean we understand it less well.

·Organizational dimensions

Irrespective of the concrete definition, world cities are produced by means of a number of underlying organizational structures. The most visible and obvious of these are the material basis on which the connectivity of world cities is built, i.e. high-quality communication, transport and logistics networks. Cities such as London, New York, and Singapore not only harbour some the world's most well connected airports, but are anchor points for extensive fibre-optic-based telecommunications networks. Bel and Fageda, for example, show how the availability of nonstop intercontinental flighthas a large influence of the location of large firms' headquarters across urban areas, confirming the importance of transport infrastructures and tacit information exchanges between world cities. Meanwhile, Malecki reveals how the geography of high-end Internet infrastructures is clearly tied to the geography of world cities. Examining key dimensions of the infrastructures needed for high-speed communication, the pattern that emerges is consistent with the rankings of world cities, with London, Amsterdam, Frankfurt, and San Francisco standing out. Meanwhile, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Singapore and Sydney are key nodes in Asia-Pacific, while Sao Paulo emerges as the best-linked location in Latin America alongside Miami, which functions as the hub for Central and South America.

Another key organizational dimension of world cities is their centrality in migration flows. These migration flows are tied to a broader social restructuring in world cities, as they are often claimed to be defined by polarized class structures comprised of“transnational elites” and a “permanent underclass”. Immigrants comprise a large and significant component of both the “transnational elites” and a “permanent underclass” in world-city class structures. This wide-ranging observation has been conceptually and empirically elaborated in subsequent research on world cities. Although the complex nature of social restructuring has cast doubt over the emergence of a straightforward “polarized and dual class structure,” rising patterns of socio-economic inequality have been recorded in world cities, and the nexus with migration has been confirmed. At the “transnational elites” end, Beaverstock explores how the expatriation of managerial elites embodies a major globalization strategy of service firms in world cities. He finds that expatriation represents a deliberate organizational strategy to develop, manage, and diffuse idiosyncratic knowledge between world cities, the major objectives of which are to service the client and increase profitability and market share. Thus the large number of high-skilled migrants from all over the world in London's financial district is instrumental to keep London running. Yet, what is at least equally instrumental is the vast army of low-skilled workers engaged in industries that “cater to the privileged classes for whose sake the world-city primarily exists”. Wills et al. have documented this for London, noting that London's expanded low wage economy is dominated by migrant workers leading to the emergence of what may be termed as a “migrant division of labour”. As an illustration, in 2001, it was estimated that 46% of London's low wage jobs were occupied by foreign-born workers. This reliance on migrant workers is even more significant in certain sectors such as cleaning where the numbers of foreign-born workers rose from 40% in 1993—2004 to almost 70% in 2004—2005.

An increasingly important organizational dimension of world cities is their de facto emergence in terms of policy frameworks and networks. Against the backdrop of an increasingly urbanizing world,Benjamin Barber’s “If Mayors Ruled the World” claims that nation states are poorly equipped to tackle global challenges such as terrorism and climate change or poverty. According to Barber, the world's cities should/will thus lead the way to a new urban millennium of renewed democracy and sustainability. Although few social scientists share Barber's somewhat naive excitement about the liberating potential of a political/policy world centred on cities, it certainly does point to a consensus about the rising influence of cities in politico-organizational dimensions of globalization. Research on urban policy mobilities, for example, has highlighted the meaning of cities in the making of global space. Using the example of the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group (C40), which brings together mayors of mega cities to address the issue of climate change, Barthold illustrates how cities increasingly engage in networks aimed at “global policy-learning” through the exchange of experiences, best practices and innovations. She shows how C40 is functioning both (1) as a network of cities that it is pooling and multiplying the particular authority, fiscal competency and technical expertise that distinguishes cities from other scales of climate governance; and (2) as collective actor in global environmental governance as it provides city governments with access and influence on global decision making procedures and international policy circles that non-state actors usually lack.

·Case study: stratification within a global geography of world cities

The variegated and sometimes contentious nature of world-city writings implies that the very selection of a “case study” implies choosing a particular conceptual and empirical vantage point that cannot be taken to stand for the literature. Here I draw on some of my own work with Peter Taylor and other colleagues in the context of the Globalization and World Cities (GaWC) research network. In this research, we explore how one of the possible global geography of world cities looks like. To this end, we map how strongly cities are inter-connected in the global economy by drawing on Sassen’s recognition of producer service firms as the major agents of world-city formation.

Producer service firms provide the financial, professional and creative means of servicing transnational corporations in their global pursuits. These activities range from resourcing capital, to navigate multiple jurisdiction, and to developgeneric marketing strategies. These are largely accomplished through face-to-face meetings requiring work to be carried out in offices across all major cities where their clients have important interests. The skyscraper cityscapes that epitomise the world-city are the“knowledge factories” that make globalization possible through myriad inter-city communications. Thus, to map world-city-formation we investigate the offices of producer service firms across leading cities, information that is readily available on firms' website where they describe their office network to both impress potential clients and attract potential employees. From this information on offices in different cities, a data matrix is created arraying firms (the agents) against cities (where the agents do their work). From this matrix, estimates of knowledge flows (advice, direction, plans, strategies, etc.) can be generated by applying a tailored network model. The outcome is a description of global inter-city flows of financial, professional and creative knowledge that defines the organizational framework on which globalization is built.

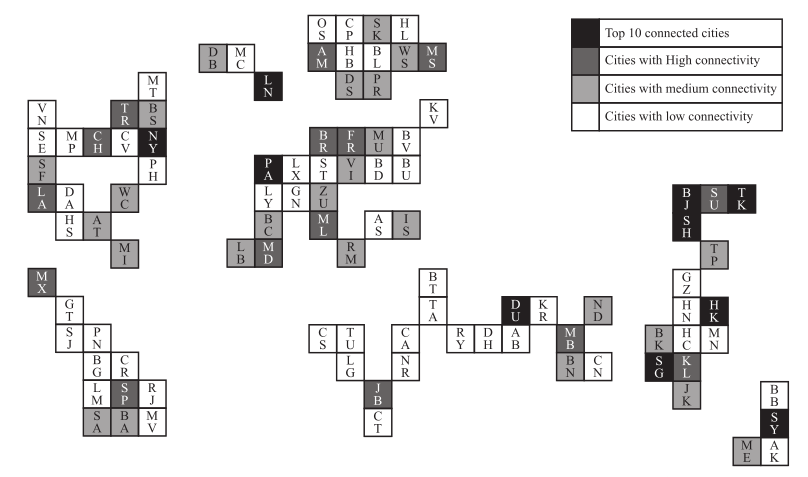

In our latest application of the model, based on a data gathering carried out in the summer of 2016, we garnered information on the size and extra-locational information of the offices of 175 service firms across 707 cities. Applying our model produces a global geography of world cities as proxies through their connectivity in the office networks of major producer services firms. This global geography is shown in Fig.1. The cartogram illustrates the most connected cities (>20%) to solve the problem of illustrating a very uneven distribution of cities across the world. In the cartogram, each city is given its own equal space in approximately its correct relative position, with darker shades reflecting stronger connectivities. Cities are indicated by intuitive two-letter codes, e.g. “NY” for New York City and “JB” for Johannesburg. The first geographical result is that there is indeed a worldwide pattern of interconnected world cities, albeit clearly an uneven one. At its simplest, the cartogram reproduces the old “North-South” divide: higher connected cities tend to be in the “North” and lower connected cities in the “South”, with the western Pacific Rim firmly bucking this trend. But the global geography is, of course, much more complicated: this simple interpretation is only a trend with many lower connectivity cities in the “North” and some higher connectivity cities in the “South”. Fig.1 illustrates clearly the three leading zones of the core of the global economy through the lens of cities: northern America, western Europe and parts of Pacific Asia. However, this is not a homogeneous core, the three zones have very different history associated with their trajectories to core status.

The oldest, indeed original, core zone is western Europe and this is reflected in two features. First, this region has more world cities than the other regions. And second, there is a wide variety of levels of connectedness amongst the region's cities, ranging from the likes of London and Paris to the likes of Leeds and Rotterdam. In other words, in this region, there is a mixture of cities of varying importance all linking into the world-city network. This is the opposite of Pacific Asia in which the connectivity levels of the cities are generally top heavy. In spite of booming and now widespread urbanization, few of these cities in the most recent of the core zones are strongly connected. Thus this region has far less world cities than western Europe, although the number increases if we add Australasian cities and Auckland to create a Western Pacific Rim region. The third core zone, northern America (i.e. USA and Canada), is in between the other two in numbers of world cities identified. However, in this case the range of levels of connectedness is very similar to western Europe with numerous less important cities such as Tampa and Charlotte joining the world-city network. But there is a regional difference in that in northern America the more connected cities tend to be in the east and west of the region, leaving the centre bereft of well connected cities apart from the major exception of Chicago.

Fig.1 A global geography of world cities as proxies through their connectivity

Beyond the core there are no regions with concentrations of highly connected cities. In Eastern Europe (the former Communist states), the most common pattern is for capital cities to take on the world-city role: apart from St. Petersburg, the only cities that feature are capital cities. Having lost its political and economic distinctiveness, this region seems to have become an appendage to the western European core, albeit that unlike western Europe there is only one well connected city (Moscow) and that there is much more concentration with generally one (capital) city per state. The same can be said for Latin America with respect to northern America where again capital cities dominate although in this case Sao Paulo, despite being neither former nor current Brazilian capital city, has become a highly connected world-city in its own right. Together with Mexico City, this city stands out in Latin America. This pattern is also found in South Asia and the large North African/West Asian region, where Mumbai and Dubai as non-capital cities have become highly connected world cities. Sub-Saharan Africa has few cities on this particular map, but it does sport a clear regional leading city in terms of connectivity: Johannesburg.

As indicated, different empirical approaches highlighting different factors of alleged global prominence have been produced. Diéz-Pisonero et al., for example, highlight the convergence between economic and cultural spheres in world cities, known as the “cognitive-cultural economy,” and use this to develop a Synthetic Index of Cultural Components. Many other alternatives exist, while it is important to point out that such mappings do not represent what world-city research is about. Nonetheless, such mappings of cities in globalization can be used as a starting point to make analytical connections to a number of other pertinent world-city research agendas. For example, these connectivity measures can be used as the input to analyses of how, and to what degree, world-city-formation is linked to rising inequality in general or migrant division of labour in particular. It also allows exploring how and to what degree this global geography is related to other geography of global inequality. But above all, it can be used as a backcloth for in-depth analyses of the making of world cities. Lai’s research provides a clear-cut example of this. Her qualitative research into a changing China helps us understand the very distinctive world-city pattern in China discernable in Figure 1, with Shanghai and Beijing—combined with the “special administrative region” Hong Kong—dwarfing the rest of the 100-or-so Chinese cities with more than 1 million inhabitants in a “tri-primate” world-city pattern of global connectivity. Lai shows how this pattern is co-produced by the sheer size of the national market, making it difficult to operate from a single city; its historical and on-going political divisions, with Hong Kong still operating as a quasi-autonomous area in financial and economic terms; boosterist visions of severe inter-city competition among some of China's urban elites, which have lead to the active pursuit of world-city status in Shanghai; and functional divisions of labour as the Chinese political system imposes a context where key agents need to be near the centre of political decision-making in Beijing irrespective of commercial opportunities in Shanghai or Hong Kong.

·Conclusion and future research agendas

Research into“world cities” has been one of the major ways in which urban studies havebecome rooted in globalization debates in the social sciences from the 1980s onwards. A straightforward interpretation of the success of this research field is that it directly confronts the commonplace observation that contemporary urban life cannot be properly understood without making some sort of reference to “globalization”. This has led to a wide-ranging literature that produced a number of new and exciting insights. However, two points to be emphasized when appraising the success—in terms of cross-referencing—of the literature invoking the world-city concept.

First, to a large extent, the literature lacks a central paradigm and often offers not much more than a very broad background to frame more concrete research into very different topics. Indeed, the most apt definition of world-city research is simply that what those researchers using the term “world cities” do: the praxis of doing research defines the evolving research subject and prevails over a rigid definition or conceptualization of what a world-city is, how it should be researched, and how one should interpret the results. Even the most widely cited world-city contributions—Friedmann, Sassen, and Taylor are best understood as specific building blocks within an increasingly diverse literature on cities in globalization.

Second, even the most basic conceptual and empirical building blocks continue to be contested, and the continued popularity of the term therefore also somewhat paradoxically stems from it having become a rallying point for radically different approaches towards understanding globalized urbanization. Indeed, a large number of references to the world-city literature stem from publications lamenting the provincialism of world-city research, which putatively narrates and possibly normalizes the urban experience of the Londons and New Yorks of this world.

The need for a more diverse literature on cities in globalization that stretches well beyond the most widely cited world-city contributions in ontological, epistemological and geographical terms cannot be disputed (for a more encompassing overview of“doing global urban studies”. However, the central tenets of the key world-city contributions still offer a useful analytical framework to help understanding globalization through an(albeit specific) urban lens. From this perspective, on-going world-city research agendas that aim to refine, deepen and extend our understanding of how (1) specific cities are key platforms in the organization of a globalised economy/society; and (2) how this impacts socio-spatial changes within those cities remain instrumental to sharpen our understanding of contemporary urban geographies. Some notable examples are contained in a recent special issue of “Environment and Planning A”; on the topic. Neal, for example, proposes refining mappings of the global geography of world cities by developing formal statistical methods for identifying well-connected cities and thus help identifying cases that warrant more detailed investigation. Meanwhile, Krijnen et al., observing a tendency in the world literature to superimpose distinctions between high- and low-skilled labour and between North and South, use the case of Beirut to marshal the need for a more plural conceptualization of “professionals” and “elites” to include expatriate or transnational service workers. This critical probing and extension of some key ideas is also apparent in Kleibert, who, based on empirical research on producer service firms in Manila, argues that the existence of linkages as per Figure 1 does not automatically lead to an increased command and control position. Instead, and in line with Parnreiter, the attraction of lower-end services may lead to cities such as Manila and Mexico City being articulated in a dependent way in the geography of world cities. And finally, one key emerging research agenda has been to diversify our understanding of world cities by revealing the global geographies of other corporate and institutional world-cityagents, articulated through institutional and industry-specific factors, grounded in diverse histories and path-dependent trajectories.